Chapter 16: What's Your Trampoline?

September 11th, 2001. My generation’s JFK assassination.

The world was never the same afterward, and most of us remember exactly where we were when we first heard the news.

Do you remember where you were on 9/11?

I was a few minutes late to school that day. On my way to class, I ran into Mr. Felicello, my high school basketball coach. He told me that as he pulled into the parking lot, he'd heard on the radio that someone had crashed a plane into the World Trade Center.

I remember thinking it was probably some guy in a private plane who was drunk or messed up on medication or something like that. Not a big deal. Minutes later, the loudspeaker announced a second plane had hit the Towers. It was a big deal.

At the same time, about 100 miles south of me, a five-year-old boy named Noam Saul was running for his life through the streets of midtown Manhattan with his father, his older brother, and tens of thousands of others.

Minutes earlier, Noam had been in his first-grade classroom when an explosion shook the building and heat from a fireball pressed through the windows. He could see smoke and fire pouring from the World Trade Center, and people jumping. His classroom at PS 234 was about five short blocks from the Towers—less than a third of a mile away.

Noam’s teacher led the class down to the school lobby. Meanwhile, his father came back to that same lobby, where he’d just dropped off Noam and his older brother. They reunited and took off through the ash-filled air, making it home safely together.

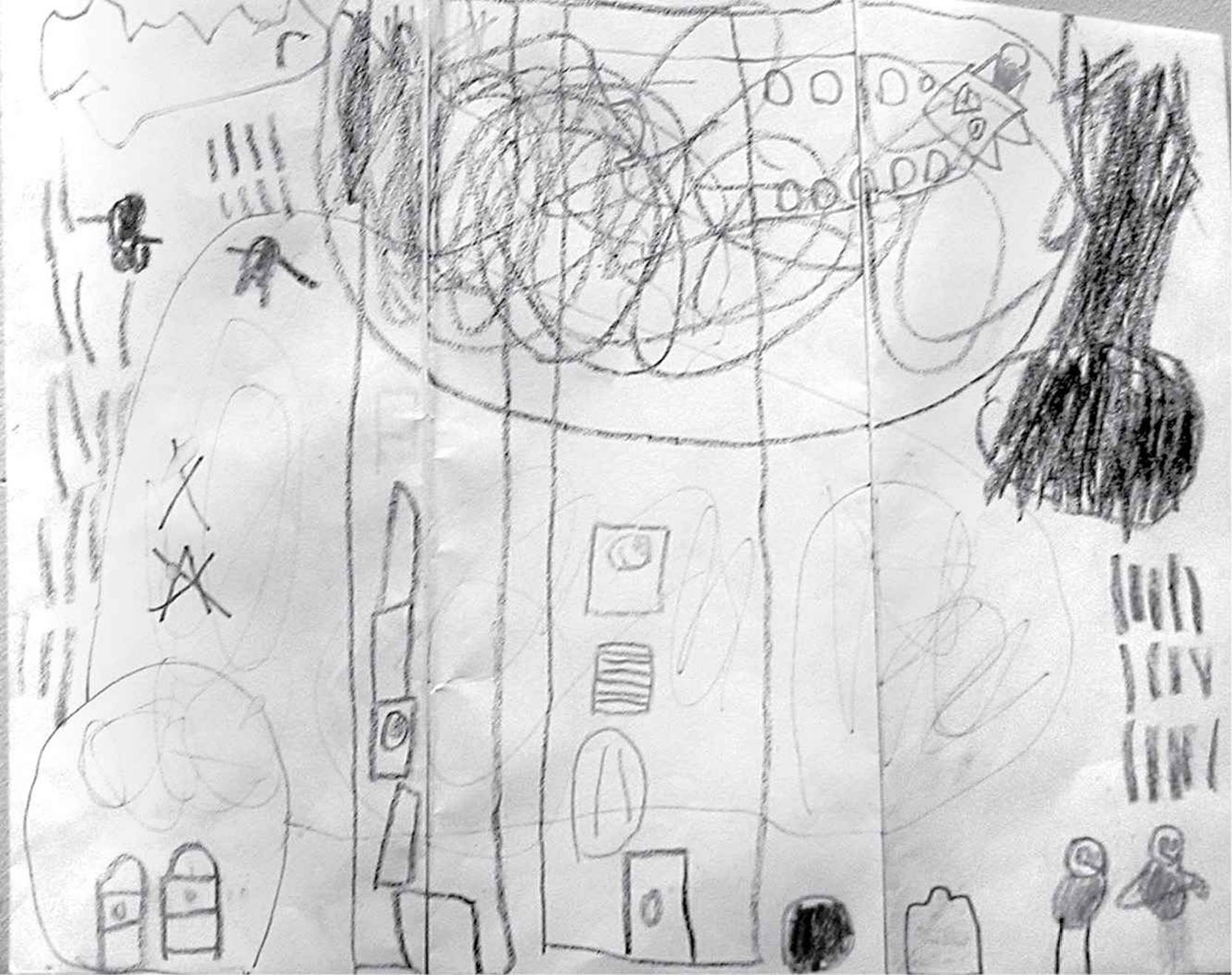

The next morning, September 12th, Noam woke up and started drawing. He drew what he’d seen the day before: a plane hitting a building; smoke and fire; firefighters; people jumping from windows.

Noam’s parents happened to be friends with psychiatrist Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a specialist in trauma.

Years later, when I began an eight-month training with Dr. van der Kolk, he shared what happened next:

September 14th, 2001

Bessel told the story of how, three days after 9/11, he was in New York City visiting Noam’s parents.

That day they walked through the pit where the Twin Towers had been and got a firsthand view of the destruction.

That night, when they returned home, Noam was still awake and proudly showed “Uncle Bessel” the picture he'd drawn the morning of September 12th.

Bessel was in awe.

He said, “This is an amazing picture, could I have it?”

“No,” Noam said.

Bessel said, “Well, let me explain, I’m writing a book and this picture HAS to go into that book, and so if you give me this picture you’ll be a famous man! Your picture will be all over the world. Will you give it to me?”

“No,” Noam said. “I’ll sell it to you.”

“How much?”

“One hundred dollars.”

“Nobody’s ever paid a kid a hundred dollars for a drawing!”

“Take it or leave it.”

Bessel laughed and handed over the hundred dollars. The drawing captivated him. At the top, a plane flew into the World Trade Center. On the left, people jumped from the buildings. In the upper right, a black mass hung in front of the airplane.

“What’s that black thing over there in front of the airplane?” Bessel asked.

“Oh, that’s the heat!” Noam said. “When the airplanes hit, there was this fireball. The heat came through our classroom window and we thought we were going to burn up.”

Bessel thought, yep that’s how people remember trauma, not as a story but as a sensation. Then he noticed a black circle near the base of the buildings.

“What’s this little black circle over there?”

“Oh that's a trampoline”

“What's a trampoline doing there?"

“So next time people jump out of the World Trade Center they'll be safe.”

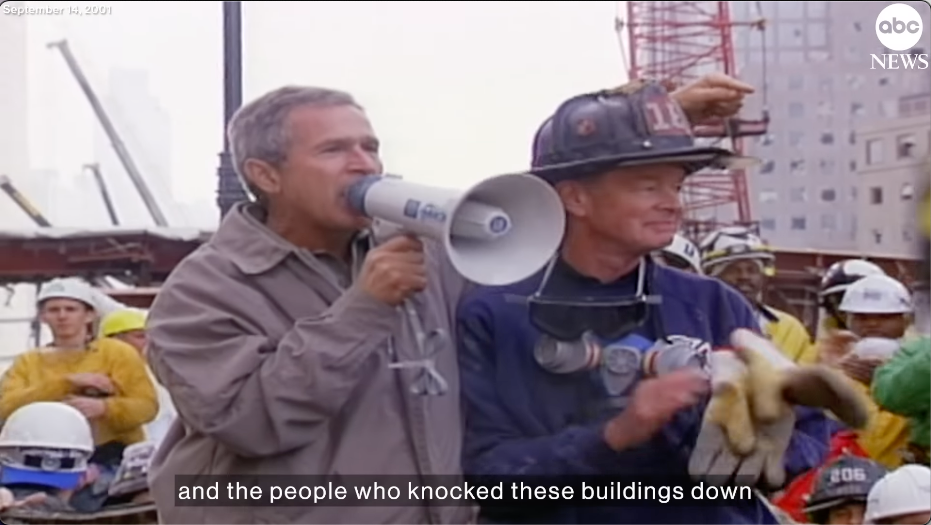

Bessel was stunned. His mind went back to the Ground Zero speech he had watched that morning—the President on a megaphone:

“I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!"

Thunderous applause followed, and chants of “USA, USA, USA."

Watching it, Bessel had thought: "Yes, this is one of the normal responses to trauma, anger, a desire for retaliation. Creatures of all species respond to threats this way. This is the 'fight' in fight-or-flight."

Now, with Noam and the drawing in front of him, Bessel thought,

"This five-year-old kid has a more evolved response than our elected leaders! He’s already asking the higher-level questions:

‘What happened here? And what can we do to prevent this from happening in the future?’

This five-year-old is imagining other outcomes!"

Present Day

When I first heard this story from Bessel, I was stunned too.

How did this kid go from the middle of the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history to—within 24 hours—processing it and coming up with creative solutions to save lives next time?

In the book The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel explains that after trauma people often get stuck in a narrowed view of reality. That lens colors everything and shrinks imagination. People stop looking at how else things can be done.

He also laid out four things that helped Noam recover and thrive:

- Immediate support during the event

- Taking an active role in escaping the threat (mobilizing the body)

- Connection with loved ones (a safe home base)

- Imagining alternate outcomes

In the first 24 hours after the event, Noam’s nervous system was flooded with messages confirming:

- I am loved

- I am valued

- I am part of a community that has my back

- I am in control of my body

- I can move my body away from danger

- I am not alone in this

- My family is here

- We're going to make sense of this together

- I am safe tonight

- I can imagine a better ending for next time

I wish my nervous system had gotten messages like that after the intense events I went through in the military.

Back then, I didn’t know that missing the right kind of soothing—and not being able to imagine another ending—would lead to years of post-traumatic stress.

How about you?

What messages did your nervous system get after the intense events you went through?

- Did you have immediate support?

- Connection with loved ones?

- The ability to move your body away from threats?

- The mental freedom to imagine another way the future could go?

If we didn’t get one or more of those experiences back then, we can bring them into our story now. In the next section, we’re not just bringing the story home; we’re giving it a new home.

Each of our stories has a "trampoline": a piece we can add, a plot twist, or a new ending we can write.

That ending will give our nervous system a felt sense of confidence and redemption.

What's your trampoline?

Let’s find out in Chapter 17: We Decide Our Future Past